By Russell Dowling, Carisse Hamlet and Thomas Matte from the Vital Strategies Environmental Health Division.

Access to safe drinking water remains one of the most basic yet essential health needs around the globe. Since 1990, the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) have periodically estimated national, regional and global progress on drinking water. Some trends are encouraging. From 2000 to 2015, experts estimate that an additional 1.6 billion people gained access to improved water sources. This brings the global population using improved water sources to more than 6.5 billion and represents one of the fastest and most significant improvements in access to a basic public health service.

The lion’s share of gains in improved water access results from a rapid shift of the world’s population into urban areas. City dwellers have higher rates of access to utilities like drinking water and electricity because these services are more easily supplied to clustered populations than to dispersed households in rural areas.

Despite this unprecedented improvement in water access, there is still much work to be done. Unsafe drinking water is still responsible for an estimated half million deaths from diarrheal illness each year. It is currently estimated that 844 million people lack access to even a basic drinking water service. Of these people, 263 million spend over 30 minutes per round trip water collection from improved sources, and an additional 159 million still collect surface water directly.

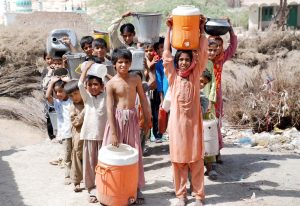

Children in Sukkur, Pakistan

Furthermore, to fully realize the public health returns of greater access to improved drinking water, routine water quality surveillance – testing for contaminants, analysis and use of data to ensure safety – must be greatly expanded. New global metrics to track progress recognize this need, introducing the category “safely managed drinking water,” which is essentially improved drinking water covered by water quality surveillance and meeting basic parameters for safety. Currently, the data needed to determine if a water source is safely managed is only available for 35% of the global population; the drinking water quality of the remaining 4.9 billion is uncertain.

People drinking from a public tap in Agra, India

Improved Access, but Safety Not Guaranteed

Though limited data exist in low- or middle-income countries, preliminary research on water quality suggests that we might not be doing as well as we would like. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis assessing several hundred studies found that while odds of contamination were considerably lower for improved sources than unimproved sources, 38% of available samples from improved sources still contained fecal contamination. A WHO bulletin echoed this finding, arguing that improved access doesn’t reliably predict microbial safety.

Even in wealthy countries, improvements are needed in water quality management. A recent study published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the US found that between 3 and 10 percent of the country’s water systems did not meet safe drinking water standards in each year since 1982. The study also found that in 2015 alone, as many as 21 million Americans may have been exposed to water not meeting health-based standards. A severe example of the effects of unsafe drinking water can be seen in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1993. Contamination from the pathogen Cryptosporidium led to the largest waterborne disease outbreak in documented US history. The failure of the city to properly treat its municipal water system resulted in illness including cramps, fever, diarrhea and dehydration for an estimated 403,000 residents.

Clean Water Saves Lives

Events like the public outrage to the Milwaukee outbreak are a testament to just how successful public health interventions on water quality — water treatment and chlorination — have been. Safe drinking water is now recognized as a public good, and when expectations fail to be met, people mobilize to hold those responsible accountable.

After Jersey City, New Jersey, became the first city in the United States to routinely monitor and disinfect community drinking water in 1908, thousands of cities across the US followed, supplementing disinfection with protected water sources and regular monitoring. The resulting decrease in the occurrence of infectious diseases such as cholera and typhoid was dramatic. The annually estimated 100 cases of typhoid fever per 100,000 people in 1900 had decreased to 33.8 per 100,000 by 1920, and 0.1 per 100,000 by 2006.

Fecal or priority chemical contamination may not have been identified without routine water quality testing or surveillance. Furthermore, such efforts can be highly cost-effective, likely reducing long-term healthcare, productivity and societal costs associated with exposure to waterborne illness-causing agents and heavy metals such as lead. The WHO even found that the global economic return on water expenditure is 2 US dollars for every 1 dollar invested.

A water treatment plant

Challenges and opportunities ahead

While innovative technologies and cost-effective surveillance systems are presenting new opportunities for ensuring water safety, climate change, industrial pollution, urbanization and population growth present a host of potential challenges. As climate change leads to more frequent and severe events like floods, hurricanes, and droughts in nearly every corner of the world, opportunities for the introduction and proliferation of contaminants in the world’s drinking water are more present than ever.

To guard against these threats, continued urbanization creates the potential for rapid expansion of access to treated, safely managed drinking water. To realize this potential, aid and investments in expanded urban water quality surveillance are needed now—not tomorrow—to adequately serve expanding and increasingly vulnerable populations in cities.

In 2010 the United Nations General Assembly declared safe and clean drinking water “a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life.” Monitoring urban water quality can help make this right a reality and prevent hundreds of thousands of deaths and improve the quality of life for millions across the globe.

CityHealth Perspective is a blog series that examines the importance of urban policies and environments on public health. Urban interventions are a strategic focus for our work and a core strength of our team. With the majority of the world’s population now urban and an additional 2.5 billion urban dwellers anticipated by 2050, we believe that public health must play a stronger role in shaping future cities that advance human and planetary health.